ZeroMq, or 0Mq if you prefer, is considered 'sockets on steroids'. The framework is aimed at simplifying distributed communications, serves as a concurrency framework, and supports more languages than any normal mortal would ever require.

http://zeromq.org

The topic of this post will be guiding through the installation on Ubuntu 12.04 and writing enough example code to verify all is happy. Future posts will focus on installation of alternative, and interesting, languages with the overall intent of demonstrating interoperability between the languages.

Let's get started;

Our target installation machine is Ubuntu 12.04 64-bit Desktop edition;

http://www.ubuntu.com/download/desktop. Your mileage may vary with alternative distributions. I'm starting with a new default installation and will work through the installation process from here on.

$ sudo apt-get install libzmq-dev

After the APT package handling utility is done humping package installations you should have a function, albeit dated, version to begin working with.

While ZeroMq supports a plethora of languages, the focus of this post is on C++. That said, we'll need to install GCC C++ compiler.

$ sudo apt-get install g++

As I said earlier, the Ubuntu repository has a fairly old version. At time of this writing, v3.2.3 was the latest stable release but for the purposes of this post we'll continue to use this version.

Let's confirm what version we have by authoring our first C++ application and ensure we can successfully compile/link with the installed libraries.

Start with a simple Makefile;

$ cat Makefile

CC=g++

SRCS=main.cpp

OBJS=$(subst .cpp,.o,$(SRCS))

INCLUDES += -I.

LIBS += -lpthread -lrt -lzmq

.cpp.o:

$(CC) -c $<

main: ${OBJS}

${CC} ${CFLAGS} -o $@ ${OBJS} ${LIBS}

clean:

${RM} ${OBJS} main

And now let's look as a trival main program that confirms we can compile/link with Zmq libraries;

$ cat main.cpp

#include

#include

int main(int argc, char* argv[])

{

printf("(%s:%d) main process initializing\n",__FILE__,__LINE__);

int major, minor, patch;

zmq_version (&major, &minor, &patch);

printf("(%s:%d) zmq version: %d.%d.%d\n",__FILE__,__LINE__,major,minor,patch);

printf("(%s:%d) main process terminating\n",__FILE__,__LINE__);

}

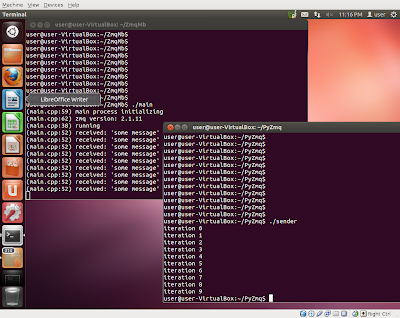

Running it confirms the installed Zmq libraries are near ancient, but again ok for our short-term purposes.

$ ./main

(main.cpp:6) main process initializing

(main.cpp:6) zmq version: 2.1.11

(main.cpp:6) main process terminating

Let's extend this to make it a bit more interesting, classic sender/receiver communication model using the PUB/SUB comm model provided by ZeroMq.

$ cat main.cpp

#include

#include

#include

#include

#include

#include

void* ctx=zmq_init(1);

char* EndPoint="tcp://127.0.0.1:8000";

static const int N=100;

static const int BufferSize=128;

void* sender(void*)

{

printf("(%s:%d) running\n",__FILE__,__LINE__);

void* pub=zmq_socket(ctx, ZMQ_PUB);

assert(pub);

int rc=zmq_bind(pub,EndPoint);

assert(rc==0);

for(int i=0; i {

char content[BufferSize];

sprintf(content, "message %03d",i);

zmq_msg_t msg;

int rc=zmq_msg_init_size(&msg, BufferSize);

assert(rc==0);

rc=zmq_msg_init_data(&msg, content, strlen(content), 0,0);

assert(rc==0);

printf("(%s:%d) sending '%s'\n",__FILE__,__LINE__,content);

rc=zmq_send(pub, &msg, 0);

assert(rc==0);

::usleep(100000);

}

}

void* receiver(void*)

{

printf("(%s:%d) running\n",__FILE__,__LINE__);

void* sub=zmq_socket(ctx, ZMQ_SUB);

assert(sub);

int rc=zmq_connect(sub,EndPoint);

assert(rc==0);

char* filter="";

rc=zmq_setsockopt(sub, ZMQ_SUBSCRIBE, filter, strlen(filter));

assert(rc==0);

for(int i=0; i {

zmq_msg_t msg;

zmq_msg_init_size(&msg, BufferSize);

const int rc=zmq_recv (sub, &msg, 0);

char* content=(char*)zmq_msg_data(&msg);

printf("(%s:%d) received: '%s'\n",__FILE__,__LINE__,content);

zmq_msg_close(&msg);

}

}

int main(int argc, char* argv[])

{

printf("(%s:%d) main process initializing\n",__FILE__,__LINE__);

int major, minor, patch;

zmq_version (&major, &minor, &patch);

printf("(%s:%d) zmq version: %d.%d.%d\n",__FILE__,__LINE__,major,minor,patch);

pthread_t rId;

pthread_create(&rId, 0, receiver, 0);

pthread_t sId;

pthread_create(&sId, 0, sender, 0);

pthread_join(rId,0);

pthread_join(sId,0);

printf("(%s:%d) main process terminating\n",__FILE__,__LINE__);

}

Running this beauty will result in the following;

$ cat /var/tmp/ZmqMb/main.log

(main.cpp:59) main process initializing

(main.cpp:62) zmq version: 2.1.11

(main.cpp:15) running

(main.cpp:29) sending 'message 000'

(main.cpp:38) running

(main.cpp:29) sending 'message 001'

(main.cpp:52) received: 'message 001'

(main.cpp:29) sending 'message 002'

(main.cpp:52) received: 'message 002'

(main.cpp:29) sending 'message 003'

(main.cpp:52) received: 'message 003'

(main.cpp:29) sending 'message 004'

(main.cpp:52) received: 'message 004'

(main.cpp:29) sending 'message 005'

(main.cpp:52) received: 'message 005'

(main.cpp:29) sending 'message 006'

(main.cpp:52) received: 'message 006'

(main.cpp:29) sending 'message 007'

(main.cpp:52) received: 'message 007'

(main.cpp:29) sending 'message 008'

(main.cpp:52) received: 'message 008'

(main.cpp:29) sending 'message 009'

(main.cpp:52) received: 'message 009'

(main.cpp:29) sending 'message 010'

(main.cpp:52) received: 'message 010'

(main.cpp:29) sending 'message 011'

(main.cpp:52) received: 'message 011'

You'll notice that the first message was lost. I've never had a sufficient understanding of why this happens, but typically the first message can be lost, primarily due to the pub/sub sockets not necessarily being fully established. Issuing a 'sleep' between socket creation and between the receiver and sender socket usage doesn't solve the problem, it's more involved than that and I have little to offer as an explanation.

So, there you go; a simple usage of ZeroMq.

Cheers.